Last modified:

Sunday, 26-Aug-2018 13:01:22 UTC. Authored by: Rebecca J. Parker (rjp43 at pitt.edu | Twitter: @bcpkr396) Edited and maintained by: Elisa E. Beshero-Bondar

(ebb8 at pitt.edu). Powered by firebellies.

Last modified:

Sunday, 26-Aug-2018 13:01:22 UTC. Authored by: Rebecca J. Parker (rjp43 at pitt.edu | Twitter: @bcpkr396) Edited and maintained by: Elisa E. Beshero-Bondar

(ebb8 at pitt.edu). Powered by firebellies. Last modified:

Sunday, 26-Aug-2018 13:01:22 UTC. Authored by: Rebecca J. Parker (rjp43 at pitt.edu | Twitter: @bcpkr396) Edited and maintained by: Elisa E. Beshero-Bondar

(ebb8 at pitt.edu). Powered by firebellies.

Last modified:

Sunday, 26-Aug-2018 13:01:22 UTC. Authored by: Rebecca J. Parker (rjp43 at pitt.edu | Twitter: @bcpkr396) Edited and maintained by: Elisa E. Beshero-Bondar

(ebb8 at pitt.edu). Powered by firebellies.When we work together on a computer file, we need a way to save it that helps to keep track of each change made to it,

so our work is stored safely and so we do not create many different copies of the same file and get confused trying to figure out

which is the most current or the best one to keep. When we are working on coding projects, alone or in groups, we need to share our files in the cloud

, or a shared internet directory, and we also need to keep track of each stage of the coding process, the changes we made on our own local

computers before sharing with the group. Sometimes we have to go back and restore something we did in an early stage that we deleted later. Each saved stage of a file’s existence is a version, and there are a number of software tools available to store safely all those versions that we care about. Some of these tools are more thorough and reliable, safer to use than others, and Git is probably the most reliable and very widely used in the coding community, because of its distinctive way of storing all local changes ever made to a file.

Git is a version control system, or a system designed to manage changes to computer files by storing a memory of each version they have taken over time. Some version control systems (like Dropbox) do this in a centralized way by keeping one master copy of a file and storing all history of its changes in a single location in the cloud (remotely). In Dropbox, if two users share a file directory, and each person attempts to change the same file, they each make a change locally, but run into a problem if they try to save their file in the same shared file location in the Dropbox cloud. If they save changes at around the same time, the centralized system creates a copy of one of the files with an altered file name (usually by putting a (1) or a (2) at the end of the original filename in Dropbox), and the owners of the directory must then decide which version to keep or how best to reconcile the two versions. Git, by contrast, would record the differences between the files as a new state of the file’s existence, and that is because it is a distributed or decentralized version control system, a system in which each storage repository carries its own distinct history. People who collaborate on a project upload and download shared versions of files from a web-based storage space called a remote origin repository, but when they work with those remote files they create copies of them on their own computers in a location known as a master repository, and Git manages information about their local version history as well as their remote history.

Git basically tracks each change you have deliberately committed to a directory, like taking a set of snapshots to record the condition of each significant state change that you record every time you make a commit. Every time you commit (or save) the state of your project with Git, it basically takes a picture of what all your files look like at that moment and stores a reference to that snapshot. To be efficient, if files have not changed, Git doesn’t store the file again, just a link to the previous identical file it has already stored. Advanced Git users may quite deliberately try to keep their local working repository different from the shared remote repository because they are working on something unstable that may not be usable by their team yet. When such an advanced user is finally ready to commit a change to the remote repository, their team members may review and reject the commit if they find something wrong with it. Git connects multiple local repositories but preserves each one’s distinct version history, and when GitHub users push their local repository files to a remote repository, they make it possible for other GitHub users to pull in those files and continue to work with them, giving them new homes and local histories. The way in which Git users interact with each other and make files available through remote repositories is sometimes described as a web of trust, in which files can be developed in multiple locations and shared with others based on their merit, and can be denied or rejected when they cause problems.

So let’s say you and a team member are both updating the same XML document inside of your

shared repository. You make your changes, save them, and upload them back to the shared

repository. The problem, for most VCSs, comes when your team member is working on the

same document as you at the same time. One of you is about to have your work

overwritten; however, Git keeps that from happening. You and your fellow team member can

each upload your revisions to the same document, and Git will save two versions of the

file. If you both were working on different parts of the same document Git will

automatically merge your changes together without losing any work along the

way. If you both happen to edit the exact same segment of code Git will issue a

merge conflict to point out where the two files differ allowing you and

your team to decide what version to keep. You can even revert to an earlier version at

any time, relying on the snapshot

that Git preserved of every change ever

committed by all project collaborators.

One of the most important aspects of Git is its emphasis on local operation. Git doesn’t need to go out to the server to get the history of a project and display it for you – it simply reads it directly from your local computer. This means you see the project history almost instantly, without having to wait for server network lag. This also means that there is very little you can’t do if you’re offline. When you manage a project using Git, you keep copies of all the project files on both your local machine and the online GitHub server. You work on your local machine, periodically pushing your changes onto the server so they’ll be accessible to your project partners, and periodically pulling changes made by your project team from the server to your local machine. So as long as you have recently pulled in any changes you can work offline until you are ready to push your changes. For more information regarding what Git is and the benefits of using Git please visit the online version of Pro Git, a Git how-to guide.

Unlike the Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs), the command line (sometimes called the

shell or terminal) is the only place you can take advantage of

all the functions Git has to offer. The GUIs only implement the simplistic functionality

of Git as a means to use Git at the most basic level. For many of us the command line is

strange and unfamiliar, but it used to be the main way that people interacted with

computers before GUIs came to dominate the computer experience. The command line is a

place where people can work more freely and have many powers to process files, powers

that are usually not available or far more difficult to access in software GUI

interfaces. Think of the command line as a way to navigate and work with your computer’s

files and systems by typing commands (strings of text) at prompts, instead of using the

mouse. GitHub offers a helpful, interactive tutorial on using the Git command-line interface. To

learn more about the power tools you can work with at command line, see Lifehacker’s A Command Line Primer for Beginners

.

Below is a list of key terms you will need to understand while using Git and GitHub. Each of these terms will be discussed in greater detail throughout this tutorial, but think of this as your quick reference guide to the basics.

revision, this is an individual change to a file (or set of files). It’s like when you save a file, except with Git, every time you save it creates a unique ID (the

SHAor

hash) that allows you to keep record of what changes were made when and by who. Commits usually contain a commit message which is a brief description of what changes were made.

The above definitions are compiled from the following three sites, which can be visited for definitions of even more Git terms: kernel.org, betterexplained.com, and help.github.com

Because GitHub is a social networking site, where people post their code so that it will

be accessible to others, using it requires creating an account. You can create a free

account by navigating to github.com. You are not required to create an account using your pitt.edu address;

however, associating an educational email address with your account may give you

additional benefits (including five free private repos). To

create your account, enter a user name, email address, and password and then click the

green button that says Sign up for GitHub

. Be sure to select the free option, and

then click the green button that says Finish sign up

. After creating your

account, GitHub will prompt you to verify your email address and decide on the frequency

of GitHub email notifications. Make sure to follow the link in the verification email.

It is important while you are enrolled in this coding course that you regularly checking

GitHub so you may decide to allow all notifications (knowing you

can change this later). You will then be directed back to your account.

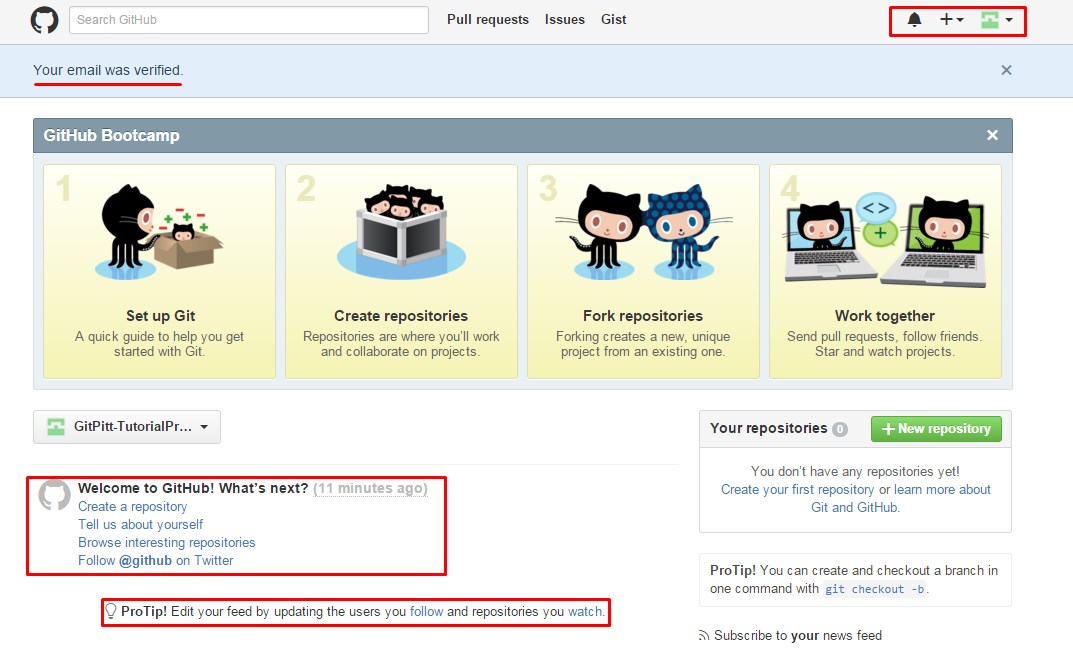

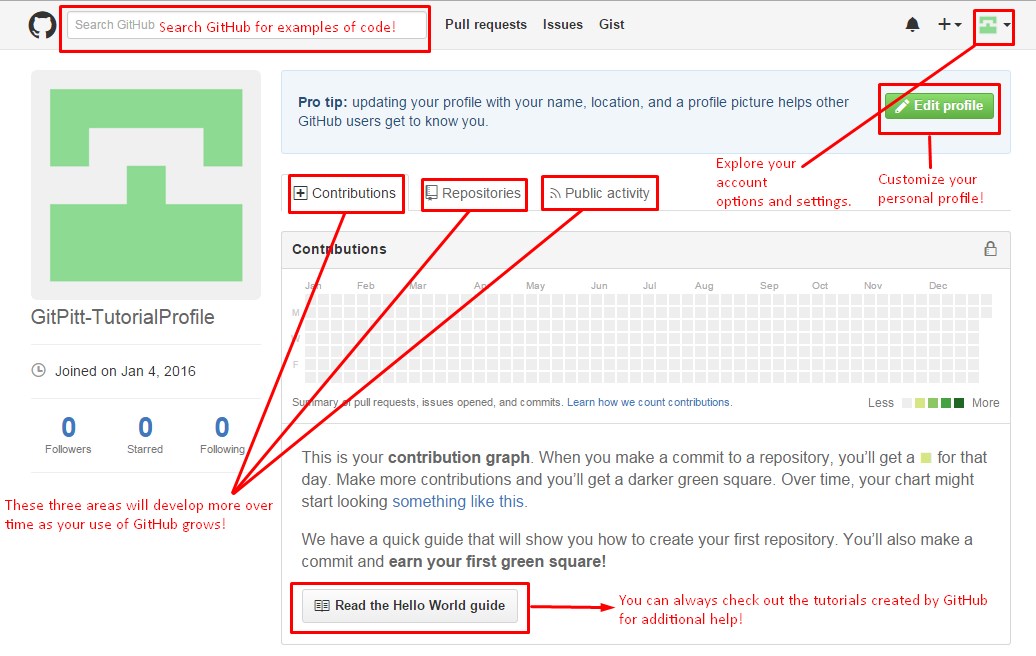

Note: We have highlighted some recommended features of your GitHub account that you should take some time exploring further.

Git is available for download on all three of these platforms: Linux, Mac, and Windows. To download Git on your local machine follow the instructions available on the git-scm.com site. Since platform downloads differ we are not going to go through a step-by-step installation process.

Our suggested settings for a Windows installation are as follows:

Adjusting your PATH environment, we recommend selecting

Use Git Bash onlyas it provides an unmodified PATH.

Configuring the line ending conversations, we recommend choosing the option to

Checkout Windows-style, commit Unix-style line endings.

Git Bash; make sure the box to create this shortcut is checked.

Installation on a Mac is much simpler. For a detailed installation guide, we suggest following this tutorial for assistance while setting up Git on a Mac.

Now that you have Git on your computer you can access it through command line. On a

Windows installation you will be using the Git Bash command shell

and on a Mac

installation you will be using Terminal

.

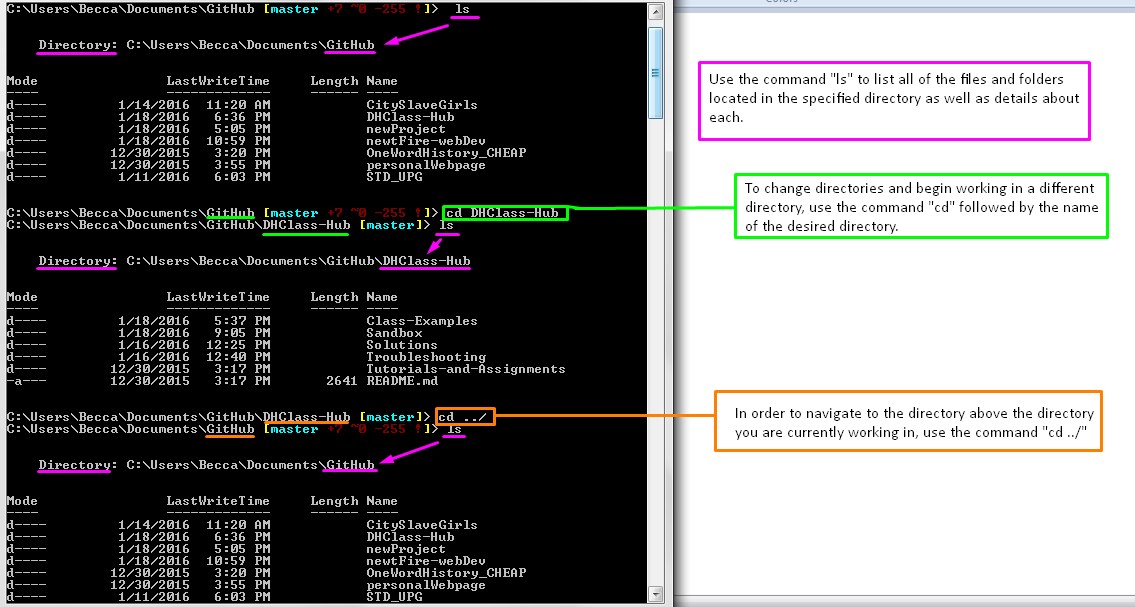

The key thing to working with Git is always knowing where to find your files in the

Finder (on Mac) / File Explorer (on Windows) and in the Terminal/Git Bash Shell. So you

need to save directories in a place where you can easily see them. In your Finder/File

Explorer, make yourself a GitHub

directory that lives inside Documents

(or

on your desktop if that is a more logical place for you). Inside the GitHub

directory you will clone each of your project repositories. In the Terminal/Git Bash

Shell), you can navigate to your GitHub

directory from the computer's root by

typing: cd Documents/GitHub/ if stored in documents or cd

Desktop/GitHub/ if stored on your desktop cd means "change

directories" and in the above command you are stepping down into Documents (or Desktop)

and into the GitHub

folder. Use ls to list out the contents of the

directory you have stepped down into.

When you first use your command shell you will need to configure Git to recognize you local computer as a correspondent to your remote GitHub account. Use the following commands to configure your local Git installation (these command can be done in Terminal/Git Bash Shell without needing to specify a directory):

git config --global user.name "YOUR NAME"Be sure to use the same email address you used when signing up for your GitHub account. This will add your name and email to a file named .gitconfig in your home directory. To verify that you entered your information correctly use the command:

git config --list.For more information on the git

config command visit the Pro Git guide on configuration. Note: in order to cache your

username and password, you may need to follow further directions found on help.github.com. To test if your information has been cached try

pushing to remote repositories that you have been added as a collaborator to on

GitHub.

Projects on GitHub are stored in repos (short for repositories), which you can think of as equivalent to folders or directories on your computer. Repos can contain plain files and subdirectories, so you can use the subdirectories to organize your project files according to whatever hierarchy makes sense to you. Initially you may want to put all of your project files into the main repo directory, and as you add additional files and your project becomes more complex, you can think about creating subdirectories and distributing the files among them according to file type or other criteria. Your project mentor will advise you about how to structure the directory space for your project.

Your remote project repo will reside on the GitHub server, which is the remote server

that is accessible to others. It is possible to edit files directly on the server using

the GitHub interface, but the typical interaction with GitHub is to work on copies of

the project files a.k.a. repo clone on your own machine and

then, when you are satisfied with the state of your work, to push (upload) your new or

modified files to the remote server so that your project partners will have access to

them. Similarly, when your project partners push their changes to the server, those

won’t be reflected in the copies on your local machine until you pull (download) them.

The process of uploading files you have modified from your local machine to the GitHub

server, and of downloading from the GitHub server files that your project partners may

have developed or modified and uploaded, is called syncing (short for synchronization).

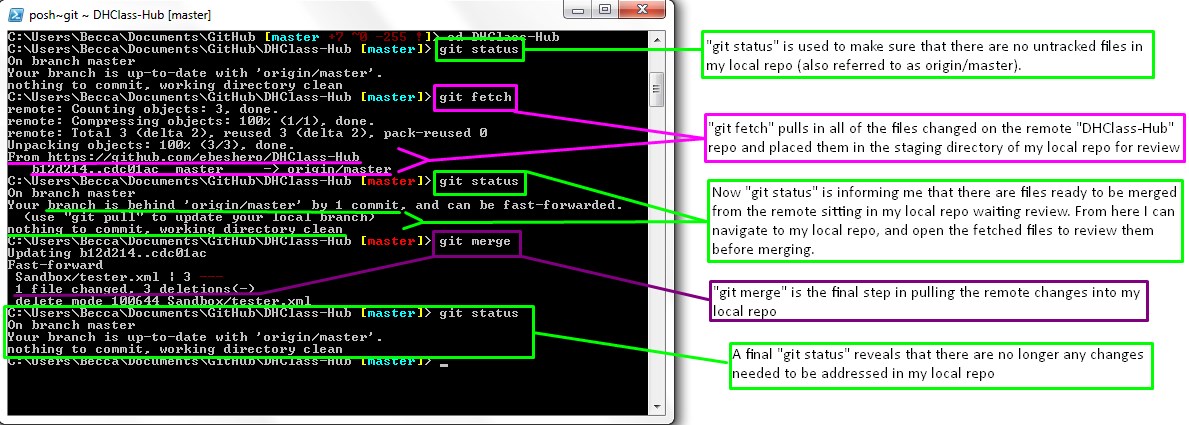

Syncing with command line requires two basic commands: git pull and

git push. The command git pull can be broken down into

git fetch and git merge, but we will discuss the

distinction later in this tutorial. When you begin a work session, you should start by

syncing your local project space with the server using git pull, so that

you’ll catch up on any changes other project contributors have made. When you reach a

stopping point in your work (when you have new or updated files

that your project partners need to see), you should commit (git

commit) and sync again, but this time using git push. You don’t

have to push after every keystroke, but you should commit regularly and push whenever

you reach a reasonably stable intermediate point to which your project partners should

have access.

The best way to initiate a new repo, for our group projects, will be to create it through the online web interface. Easy to follow instructions on how to do this can be found on help.github.com. If a repo is created through the web interface it will need to be cloned in order for you to access it and begin working on your local computer. Only one member of your project team will need to create the project repo, and all other team members will clone from that repo.

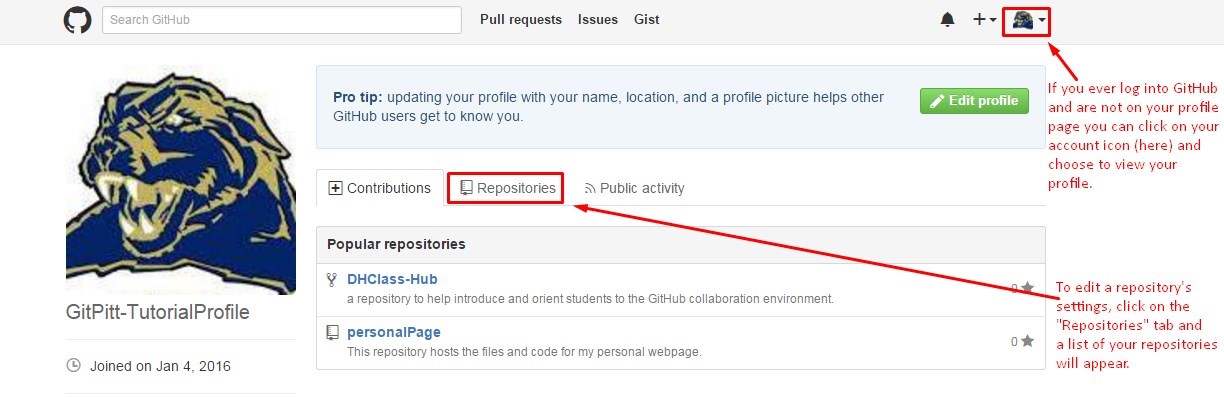

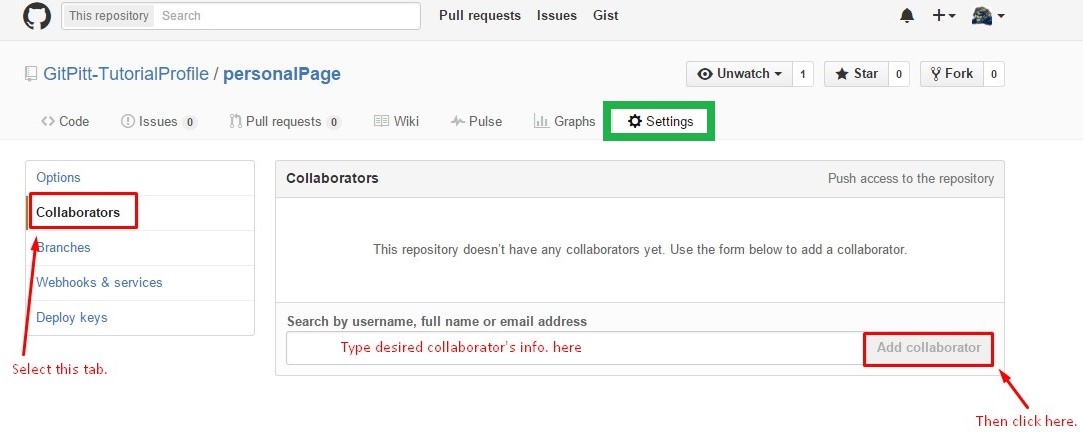

Alongside version control, one of GitHub’s most useful features is that it supports collaboration. Forget the days of emailing a file back and forth between group members as it is updated, or waiting to edit a document for fear of losing simultaneous edits. GitHub allows multiple collaborators to manage a repository. The only way to handle collaborators is through the web interface:

Settingsat the top of the screen.

Collaborators.

In the future, if collaborators need to be removed simply navigate this same path and there will be an option beside each collaborator to remove them.

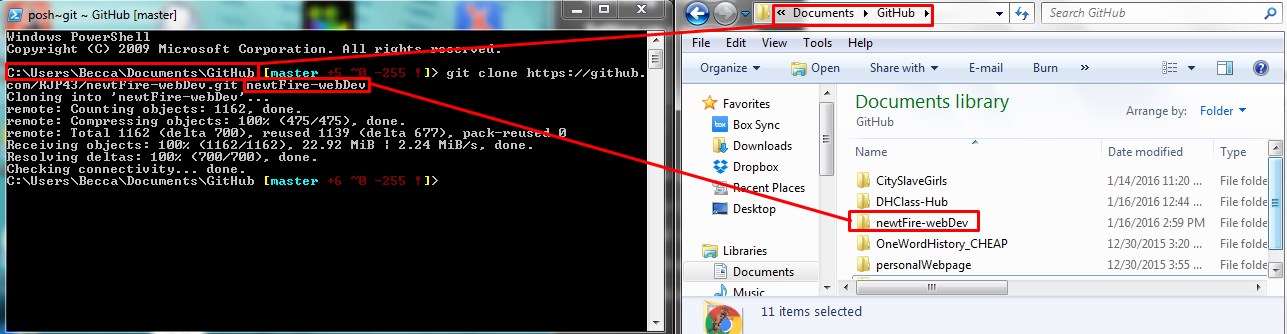

As we explain above, the way you work on your project (create files, edit files, delete files) is to work on them on your local machine and then sync any modifications to the GitHub server, so that they will be accessible to your project partners. The Git term for copying a project from the GitHub server to your computer initially so that you can begin to work on it locally is called cloning. You only have to clone a project once, when you first begin to work on it. Cloning is the copying of a project already in existence on the GitHub server to your local computer so that you can begin to work on it; whereas, syncing is exchanging updates between your local computer and the GitHub server after you’ve already cloned the repo and established a local copy in which you can work. This working model separates saving your work to your local computer (which you should do frequently) and syncing your local clone of the repo with the master copy on the GitHub server, a design that protects you from uploading mistakes to the server. That is, you do your development on your local machine, where only you have access to the files, and when you’re ready to share your work with your project partners, you sync (upload) it explicitly to the server.

Before you clone a repo, you need to understand how to navigate between directories using Git Shell. To begin you will open your Git Shell (command line / terminal interface with Git). We explain in detail how to open this above. When opening Git Shell from a shortcut link you will be placed in the main configuration folder you set up when installing Git. The following image explains how you navigate between directories:

Again, to begin, open your Git Shell (command line / terminal interface). We explain in detail how to open this above.

To clone a repo from the remote online server using command line you use one easy

command: git clone. After git clone you copy the URL of the

repo you wish to clone.

This creates a copy of the entire repository on your local machine and adds the original location as a remote so you can pull from it again and push to it if you have permissions. Note: you will only be able to directly push changes to the GitHub server if you have been added as a project collaborator. Later in this tutorial we will discuss how you can contribute to other GitHub projects that you are not a collaborator on via forking and a pull request.

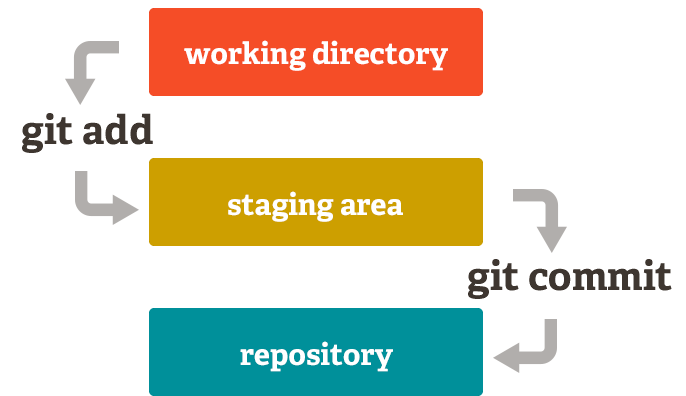

When making changes to a repo it is important to remember the three parts or your Git repo on your local machine: unstaged, staged, committed. If you make edits to a repo those changes sit unstaged until you have consciously added those changes to the staging area. This mean you could modify a file multiple times without documenting every single keystroke before asking Git to track those changes. Once you have added changes to the staging area Git will monitor if any new changes differ from what was added and mark those changes as unstaged. Staging changes allows you to review before committing.

git fetch and git merge or the single command

git pull. By using git fetch and git

merge you can first see the changes that are being brought into your

local repo (or fetched) from the remote repo. This allows for you to,

upon review, make the decision to merge those remote changes with your

local repo. The command git pull combines the two previously mentioned

commands into one step, which can be convenient yet dangerous if there is a

possibility of the changes coming in to conflict with files you may have edited

without committing.  Some believe it is best practice to review all of the

remote files you are bringing into your local repo before merging. A detailed argument for always using

Some believe it is best practice to review all of the

remote files you are bringing into your local repo before merging. A detailed argument for always using git

fetch and git merge over git pull has

been made.

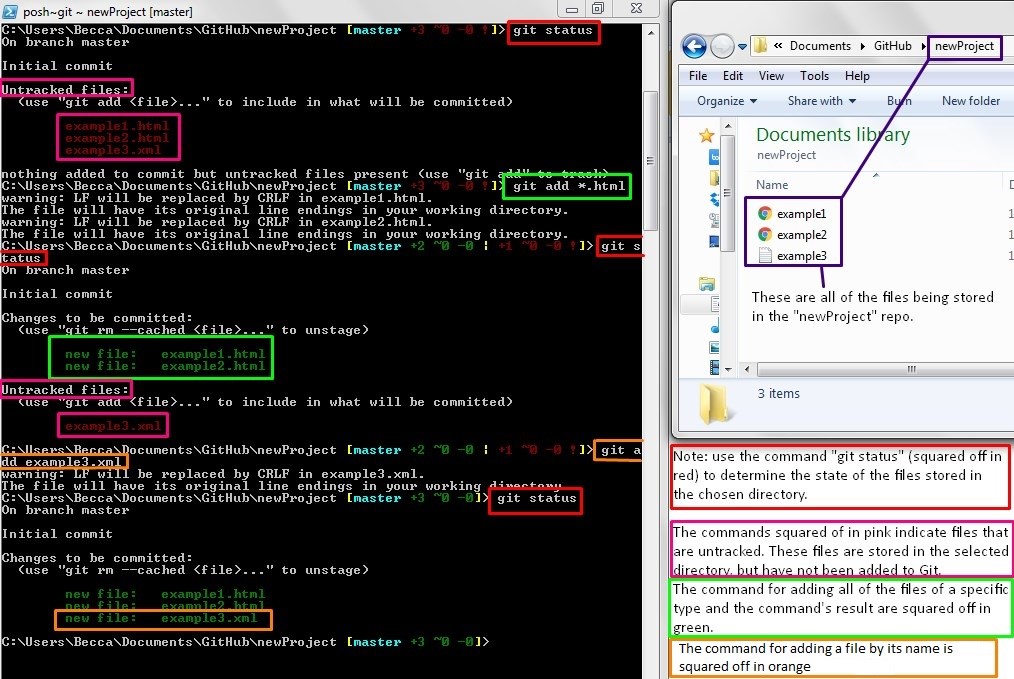

staging areaor

index. This is an intermediate area where commits can be formatted and reviewed before completing the commit. To stage a file, use the command

git add. If you want to stage all of the changed or newly

created and deleted files stored in the working directory you can type git add

-A. To specify that you only want to stage a certain type of file you use

an asterisk. For example: to stage all of the .html files you type git add

*.html. If there is only a single file you want to stage you can type the

filename after the command. For example: git add index.html.

git stash. This command stashes your changes outside of

your working directory while you pull in your partner’s remote changes. You then can

return your stashed files to your working directory and continue by adding your

changes to the staging area. For more information on git stash visit the Pro Git guide on

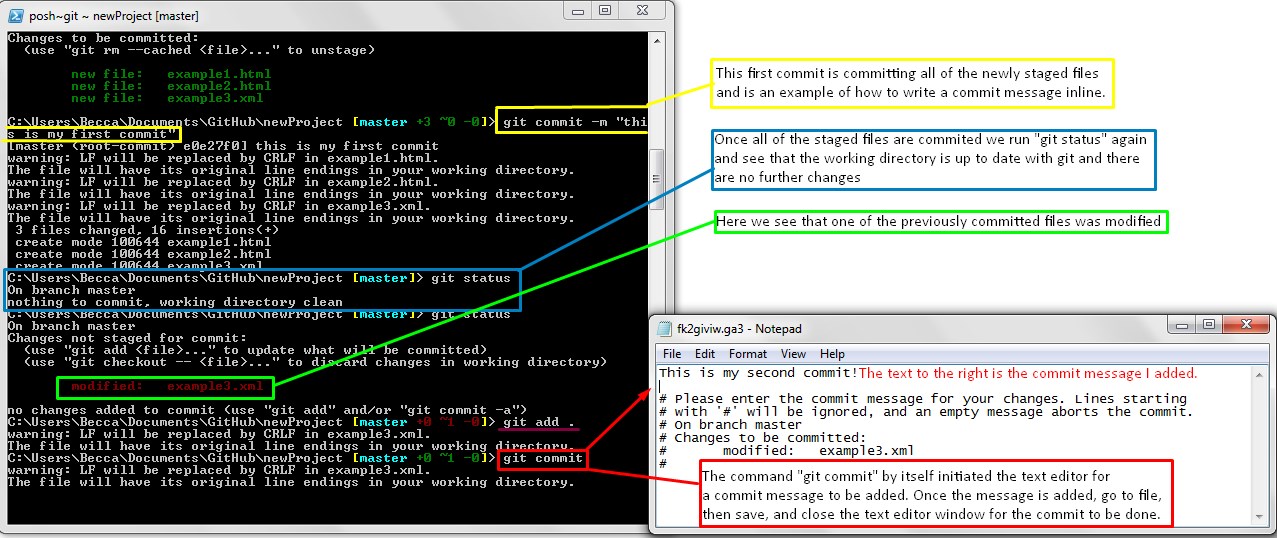

stashinggit commit. To write a commit message

right inside of Git Shell type git commit -m followed by the commit

message in quotes. Git requires a commit message when committing. Think of commit

messages as the breadcrumbs of your project for yourself and your team members;

every commit message documents changes to the project with an author and time stamp.

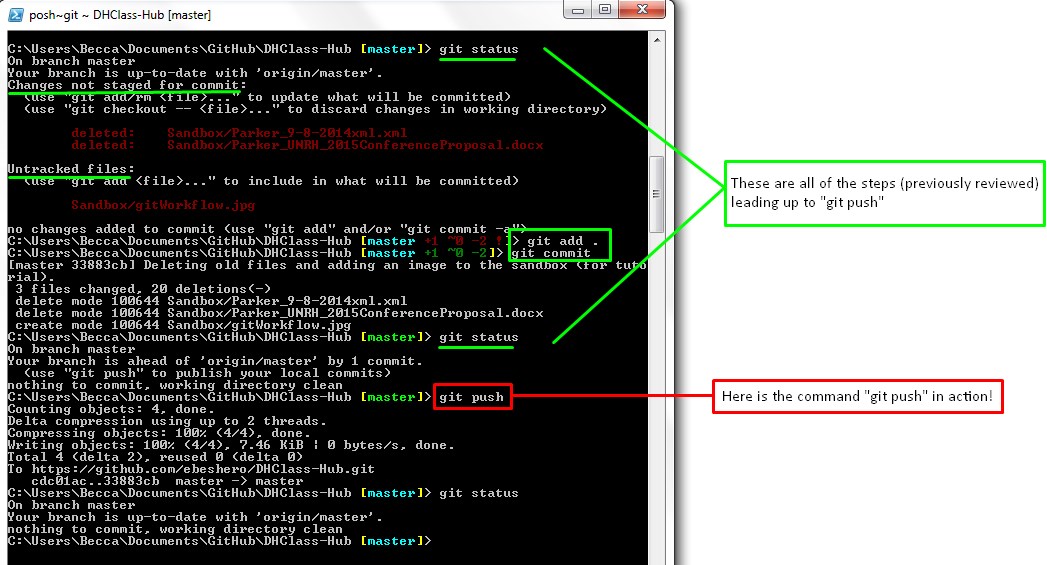

git push.

As discussed above, GitHub serves as a social media network that stores and talks to Git repositories. The GitHub interface is useful for many aspects of project management. The key parts of GitHub’s interface besides the remote storage of project files are the issues boards, wikis, and data visualizations. Wikis and issues are often used in projects to manage tasks and communicate between project team members and the GitHub community with project problems and updates. The data visualizations are helpful in mining a project’s information on collaborators and development.

To create or comment on an issue navigate to the desired repo and click on the

Issues

tab near the top of the page; notice there is also a tab for Wikis.

Issues and Wikis on GitHub are written in Markdown Language. In fact,

markdown is used for styling all forms of writing on the GitHub platform.

GitHub offers a comprehensive guide to writing markdown that we recommend you

review; however, when writing on the GitHub interface there are options similar to

Microsoft Word that can be toggled to have a specific styling applied to your text.

Besides project team communication, another important aspect of project management is

data preservation. Long-term preservation can be defined as the ability to provide

continued access to digital materials, or at least to the information contained in them,

indefinitely. A sustainable preservation program should address organizational issues,

technological concerns and the digital curation/data management process. Using Git and

GitHub already provides one means of data preservation; however, it is important to

realize that all of the data collected through the use of Git / GitHub is also important

to preserve alongside the literal files of your project. One option we have researched

to be viable for creating a backup of your Git and GitHub data is backhub.co. Another nifty tool that

we recommend you update frequently is the online digital archive of websites. By adding updates to this

site you can go back and review previous saved versions of how your website(s) looked.

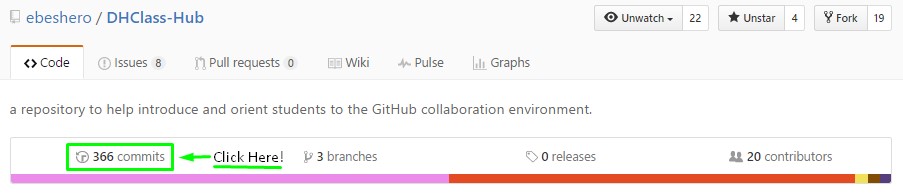

Besides data preservation it is important to also be able to mine your GitHub data. The

GitHub interface makes this really simple. In any repo, at the top of the page, there

are two tabs that are particularly useful for mining your GitHub data: Pulse

and

Graphs

. A repo’s Pulse visualizes the activity of the GitHub repo,

while Graphs visualize everything from specific user contributions to the

types of files stored in the repo. These visualizations can be useful when trying to

determine details about how the repo (and therefore project) grows and changes over

time.

We recommend our DHClass-Hub Quick Reference Guide.

Here is a list of commands used most frequently, and some options to modify the results of each command. Some of the commands listed here are associated with advanced project management while others are more basic. For commands to correct merge conflicts and bad commits please refer to our troubleshooting section. We have not listed every possible command; however we can recommend these sites to review more commands: the Pro Git Guide, siteground.com, atlassian.com, and orga.cat. Another really great thing about Git is that it has been in existence since 2005 and is used widely among computer programers; therefore, the resources on Git and Git commands are vast!

git

help: possibly the most useful Git command, this command allows you

to search the most common Git commands in the command/terminal shell. If you follow

this command with another command or concept (i.e.. git

help push) Git generates a html page detailing the command or

concept as well as possible options for its use.git

init: initializes a git repository by creating the initial .git

directory in a new or in an existing project.git

clone: copies an existing GitHub repo to local machine.git

status: checks the working directory to see if up-to-date with

the remote repo.git add:

a.k.a. staging changes, adds changes to staging area of the working directory. This

command is the first step in committing changes to your local version of the repo

before pushing them to the remote GitHub version of the repo. By adding

-A

(git add -A) Git adds, modifies, and

removes ALL entries to match the working directory. To specify that you only want to

stage a certain type of file you use an asterisk. For example:

to stage all of the .html files you type git add *.html. If

there is only a single file you want to stage you can type the filename after the

command. For example: git add

index.htmlgit

commit: tells Git to record the changes made to your version of

the repo. Every commit needs to have a message that explains what files have been

edited/added. After the command add -m and then the commit message in

quotes (git commit -m "This is where your message

goes"). You can skip the command git add by using

git commit -a -m followed by your commit message. However, best

practice is to add and commit in separate steps so you are aware of the files being

added before making the commit. If you ever find yourself annoyed with your own

commit message, before you push you can actually amend your commit using: git

commit --amend. Don't use this after you've pushed (it's like revising

history then--it would tangle up everyone's repo histories to amend once you've

pushed).git

stash: used when you want to record the current changes to the

working directory, but want to go back to a clean working directory without forever

losing those changes and without adding them to the staging area. This command saves

your local modifications temporarily outside of your working directory and reverts

the working directory to match the last commit (typically used

so you can pull in remote changes to a clean directory while avoiding possible

merge conflicts and keeping your changes available). The modifications

stashed away by this command can be listed with git stash list,

inspected with git stash show, and restored (potentially on top of a

different commit) with git stash apply. git

pull: this command is made up of two other commands (git

fetch and git merge) and is used to fetch the data from a

remote repository and merge it into your local computer’s version of the repository.

If working in a fork it is important to remember that changes are pulled from the

original remote repo the fork is made from: git pull upstream master.

When pulling from the original repo of a fork it is necessary to set that original

repo as a remote origin (called upstreamin the previous example).

Masterrefers to the branch of the original repo of which the changes are being pulled from, and can be changed to any branch name of that original repo that the desired changes reside in.

git

remote: used to retrieve a list of remote repositories associated

with local repository. To create a new remote association use git remote

add followed by a name for the remote branch (i.e. upstream) and then the

URL of the remote repo on GitHub. git remote -v displays a verbose list

of the associated remote repos with the remote URL after the repo name.git

push: updates remote repos to match commits made on local machine. If

working in specific branches you can designate the branch name (that you wish to

push) after the command, or use git push -all to add commits from all

local branches.git

branch: used to work inside of branches. This command followed by

a branch name creates a new branch. For a list of both remote-tracking branches and

local branches use git branch --list. Frequently branches are used for

experimental development that may or may not be incorporated into the master branch

of the repo. Having these changes in a branch prevents the master branch from bad

commits and uncertain files.git

checkout: followed by a branch name allows you to switch into the

working directory of a specific branch. git

diff: followed by the names of two branches allows you to compare the

differences between the two branches. For example: git diff master

development will show the differences between the master branch and the

development branch. If you want to just get a list of the files changed between the

two branches you can change the command to git diff --name-only again

followed by the names of the two branches you wish to compare.If you are reading this section you probably are at a fearful state of emergency with your project repo due to a merge conflict. The first thing that you should keep in mind however is that you can always undo the changes causing a conflict and go back to the state before the conflict occurred. Another benefit of using Git over many other VCSs is that a merge conflict will not bring your complete team to a halt or cripple your remote project repository. This is because, in Git, conflicts can only occur on a single user’s local machine. In Git, merging is the act of integrating another branch into your current working branch: most often taking changes from a remote branch and combining them with your current working directory on your local machine. Typically Git can seamlessly integrate multiple changes from multiple collaborators; yet, occasionally Git runs into a scenario where the changes overlap thus causing a merge conflict.

When faced with a merge conflict, the first step is to understand what happened. Did one

of your team partners edit the same file on the same lines as you? Did they delete a

file that you modified? Did you both add a file with the same name? Using the command

git status will tell you where you have unmerged paths

or

conflicts. The most common conflict occurs when one partner makes a change on a

particular line in a file, and a fellow team member makes a change on the exact same

line. Git does not automatically assume the last person to push changes is correct and

should over-write the other’s changes. When this sort of conflict occurs, Git writes a

special block into the file that contains the contents of both versions where the

conflict occurred. To complete this type of merge, use <oXygen> (or other text editor) to resolve the conflict, then add the

file and commit it to complete the merge. In the file, Git automatically adds conflict

markers to the affected areas. A conflict-marked area begins with

<<<<<<< and ends with

>>>>>>>. The two conflicting blocks themselves are

divided by a =======. You have several options here. You can either keep

your changes, take your partner’s changes, or make a brand new change. Whatever you do,

you need to make sure to resolve the conflict such that the file makes sense, and

everyone is happy. The goal is to get the file to look exactly how you want it. You’ll

delete the conflict markers, and just type out a new change or remove the unwanted/wrong

lines. Once you have made those changes you can use git add and follow

through with making a new commit to push to the remote. Opening the file in your editor

and cleaning it up there is perfectly valid, but can be jarring and difficult to

distinguish the changes. Using a dedicated merge tool (like Meld or Kaleidoscope)

can make this easier (if you have one installed). You can

configure your tool of choice using the git config command. Consult your

tool’s documentation for detailed instructions. Then, in case of a conflict, you can

later invoke it by simply typing git mergetool.

Outside of the above solution there are a few other ways of fixing possible merge conflicts and getting rid of bad commits. The need-to-know Git commands for merge conflicts and bad commits based on the conflict and state of the local repo are:

git stash: this takes all the changes in your working

directory and saves them on a new clipboard. Leaves the local working directory

clean; you have no more local changes. Later, at any time, you can restore the

changes from that clipboard in your working directory and continue working where you

left off. To get a list of all your stashesuse the command

git stash

list. When you’re ready to restore a saved Stash, you have two options:

use git stash pop to apply the latest stashand clear it from your stash clipboard or use

git stash apply followed by the stash name

to apply that specified stash. The second option keeps the stash on the clipboard, and it can be deleted later via

git stash drop followed by

the stash name. git

revert: is used to undo a previous commit(s) by

introducing a new commit that reverses an earlier one. This doesn’t change the

project history, which makes it a safeoperation for commits that have already been published to a shared repository (i.e. the GitHub remote repo).

git

reset: is used to undo changes in your working

directory that haven’t been committed yet. If you do not want to loose your local

changes or the changes from the commits being rolled back use git reset

--keep followed by HEAD or the commit hash ID. If you have

decided you want to be rid of all current local changes use git reset

--hard. This will cause you to loose all current local changes. If you

are unsure that you want those files best bet is to be safe and use git

stash before this command.git

clean: removes untracked files from your working

directory. This command is often executed in conjunction with git reset

--hard. Remember that resetting only affects tracked files, so a separate

command is required for cleaning up untracked ones. Combined, these two commands let

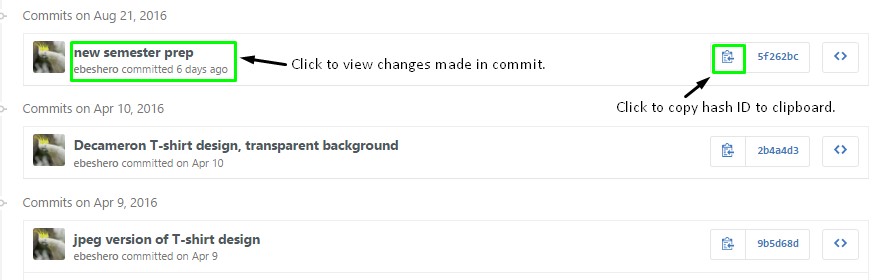

you return the working directory to the exact state of a particular commit.Note: When resetting or reverting a repo you can chose the commit to reset/revert back to

by grabbing the commit hash ID from that commit. A simple way to find commit hash IDs is

to use the GitHub interface by viewing all of the commits in a repo. If you simply want

to go back to the last commit use HEAD after the command instead of the

commit hash ID.

The atlassian.com tutorial on undoing changes, the Pro Git blog titled Reset Demystified, GitHub help guide to merge conflicts, and the git-tower.com ebook are our go-to sources for fixing and preventing merge conflicts and bad commits.

Branching means you diverge from the main line of development and continue to do work without messing with that main line. The master branch is the main branch of a project. When working in projects with multiple collaborators it may be important that the master branch not have errors, and always be in good working order. If everyone is writing new code into the master branch, it’s possible for the master branch to enter an unstable state temporarily. To avoid that, projects may require that all developers work on different parts of the project separately, in their own branches, and merge their individual development branches into the master branch only once they are confident that it won’t have a destabilizing effect. This can be useful even in single-developer projects if you need to maintain multiple versions, such as a stable branch that people should be able to download and use and a development branch that will eventually become the new stable branch, but that isn’t yet stable. Branches can be merged and deleted because a branch is an inalienable part of the repo in which it is created in; thus, working in a branch requires you to already have a cloned repo. Just to be clear, when you clone a repo that has existing branches the entire repo gets cloned including all of the repo’s existing branches.

To really understand the way Git does branching, we need to take a step back and examine how Git stores its data. As stated above, Git doesn’t store data as a series of changesets or differences, but instead as a series of snapshots. When you make a commit, Git stores a commit object that contains a pointer to the snapshot of the content you staged. This object also contains the author’s name and email, the message that you typed, and pointers to the commit or commits that directly came before this commit (its parent or parents). A branch, in Git, is simply a lightweight movable pointer to one of these commits. The default branch name in Git is master. As you start making commits, you’re given a master branch that points to the last commit you made. Every time you commit, it moves forward automatically.

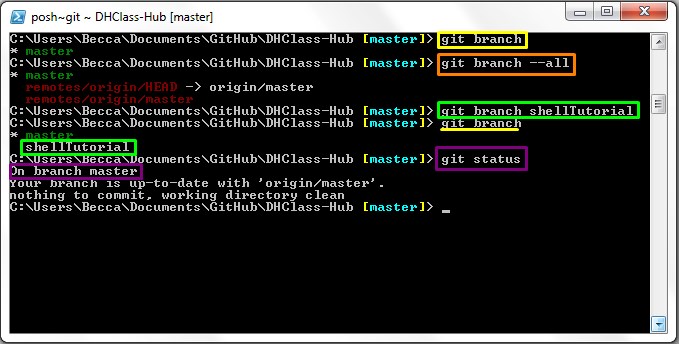

Before creating a branch it is important to note what branches are already a part of your

local repo. To do this we use the command git branch. This command lists

all the branches only in the local repo. The master branch came automatically from the

source repo upon cloning as the main branch of the repo. To see all of the local

branches, including the master branch, and the remote branches that can be pushed to we

use the command git branch --all. Now to create a new local branch use the

command git branch followed by what you wish to call the branch. For

example: git branch development will create a branch called

development

. To verify that a new branch was added, re-run the git

branch command. You should now see the new branch. The star to the left of a

branch name indicates where you are working, and this can be verified with git

status. When you run git status Git Shell should return a line

listing what branch you are on. For example: if you are working on the master branch Git

will return the line On branch master

.

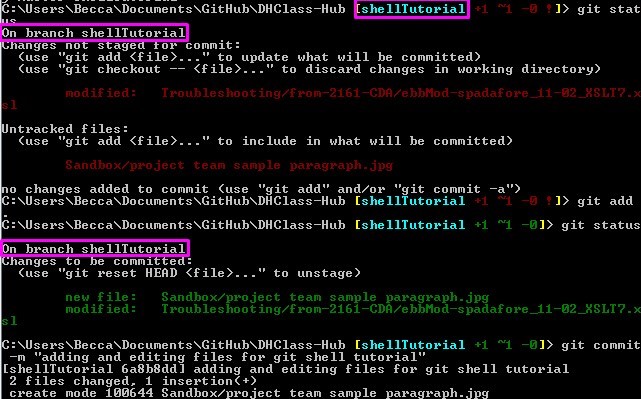

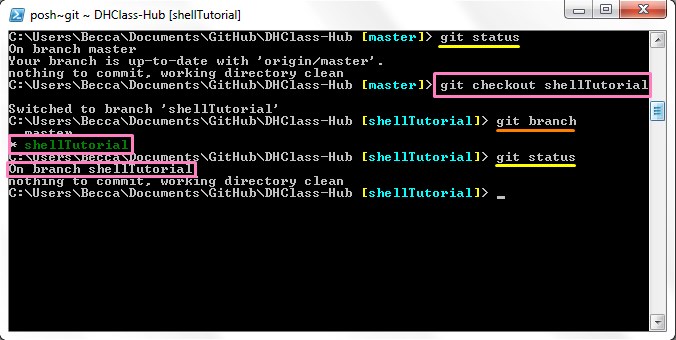

If you want work to appear under a specific branch you will need to switch to the desired

branch before committing changes. To switch branches use the command git

checkout followed by the name of the branch you wish to switch to. For

example: git checkout development will switch you over to the

development

branch.

You can verify that you have successfully switched branches by using either of the

previously explained commands: git branch or git status.

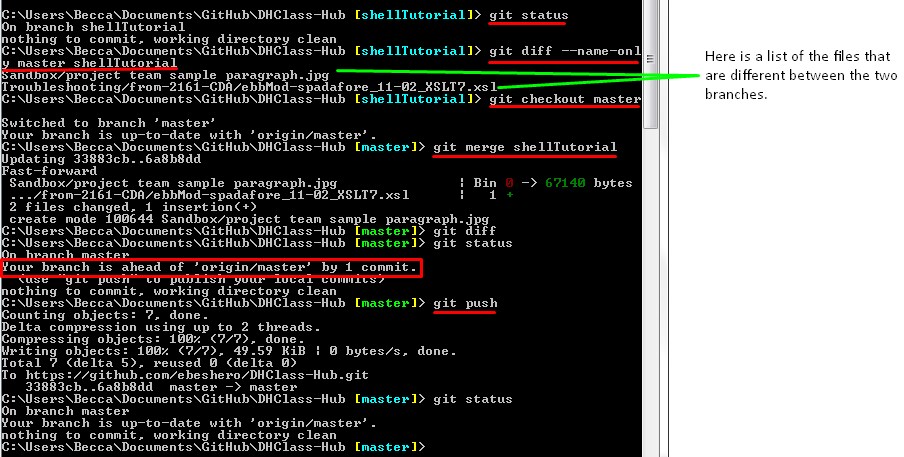

Once there have been changes made via a branch and you wish to combine those changes with the main (master) branch, you will need to do the following:

git diff followed by the names of the two branches you

want to compare. For example: git diff master development will show the

differences between the master branch and the development branch. If you want to

just get a list of the files changed between the two branches you can change the

command to git diff --name-only again followed by the names of the two

branches you wish to compare.git status or git branch to verify what branch

you are currently working in. If you are not on the master branch you should switch

to it using git checkout master.git merge command followed by the name of the branch

being merged into the master branch. For example: git merge

development.git diff again with the

two branch names, and if Git does not return anything that means there are no

differences between the two branches.git status it will show that local master is ahead of

the remote origin. To fix this and bring the remote origin repo up to date with your

local master, run the git push command.

If you have done work in a branch, and you do not want to merge the changes into the

master branch until others on your team have reviewed it you can push the branch and its

changes before merging. As long as you have the branch selected in Git Shell, you can

use the command git push origin followed by the name of the branch to

update the remote repo with the new branch. For example: git push origin

development will push the development branch and its changes to the remote

origin. Now if another collaborator wishes to clone the repo, and bring in your branch

to their local repo they will be able to do so.

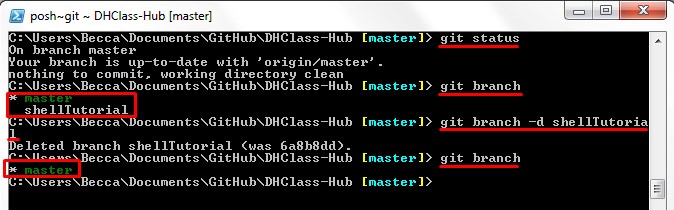

Some branches are created only temporarily; therefore, you may desire to delete a branch

before or after merging. The command git branch -d followed by the branch

name will delete the specified branch; if the branch is not fully merged in its upstream

branch or contained in the current branch, this command will fail with a warning.

Otherwise if the branch has been successfully merged with another branch then the

command will go through and the branch will be removed. Use git branch to

verify deletion. If you wish to remove the branch whether it has been merged or not the

command is altered slightly: git branch -D followed by the branch name.

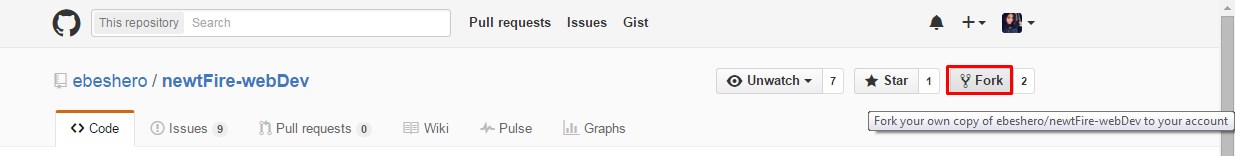

Part of the open-source etiquette of GitHub is that developers are encouraged to copy and then improve code originally created by others in a separate forked repo. GitHub supports the creation of derived projects through forking. When you fork a repo, you create a copy of it under your own account, where it acquires an independent identity. You can do anything with a repo you created by forking someone else’s project that you can with a repo you created from scratch. The moment that you create the fork, your new repo is no longer synchronized with changes in the repo from which you copied it originally. If you fork a repo and make changes that you would then like to contribute to the original source, you can issue a pull request, inviting the developers of the original repo to merge your forked repo’s changes into their original project.

To begin forking you need to navigate to the repo you wish to fork, and select the

fork

button in the top right of the page.

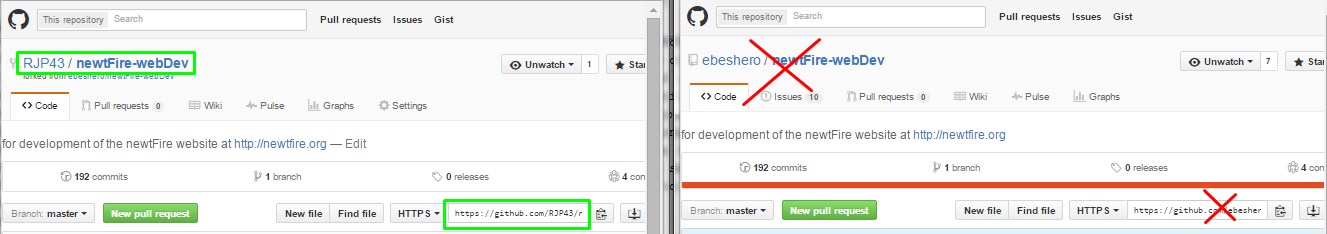

Next, you will need to navigate to the new forked repo created on your account. From

here, follow the steps above on cloning, and clone the repo using

git clone and the HTTPS of the forked repo. Make sure you are cloning

the repo that is located on your account and not the source repo you forked from.

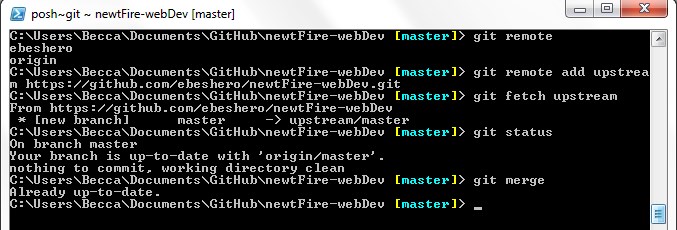

In order for the forked repo to reference the source repo, you will need to set up the

remote upstream. Do this with the following command: git remote add

upstream followed by the HTTPS of the source repo. Use the command git

remote or git remote -v to show all of the remote versions of

your repository. You should see origin

(the direct remote version of the forked

repo) and the upstream you just created. When you want to bring any new changes made on

the source repo’s master branch into your forked repo, you can use the following

commands to do so: git fetch upstream master will show the changes able to

be brought in and git pull upstream master will bring the changes in. These

commands function the same way in a fork as they do in any cloned repo.

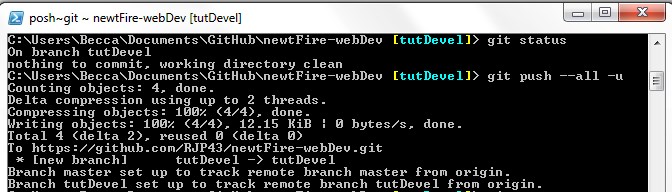

In the branching section of this tutorial we discussed why using a

branch is good practice. When working in a forked repo, branching becomes even more

important and practical. The master branch is better to be left free of

developmental/experimental changes so that it can be used to sync with the upstream

(source repo). Therefore, it is best to add and change files in branches of your fork.

After you have created a branch, modified files, and committed said changes use the

command git log --pretty=short to see a listing of commits. Finally, to

push all the local branches and change to the forked remote use the command git

push --all.

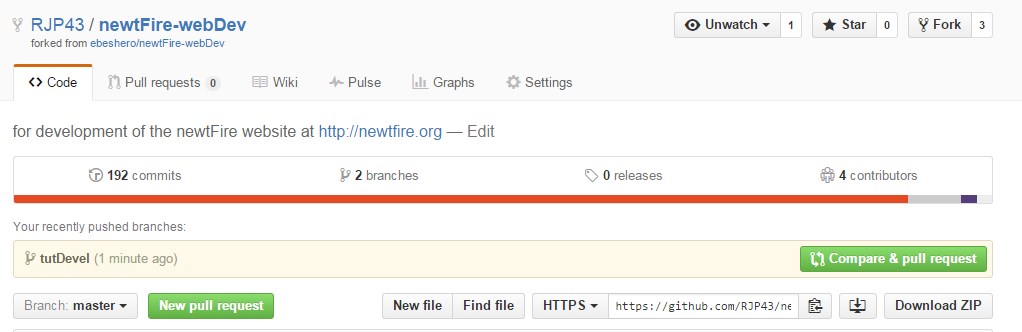

Now if you go back to your fork on GitHub, you can see that GitHub noticed that we pushed

a new branch with changes to the source repo’s code. GitHub presents us with a big green

button to compare our changes and open a Pull Request to the original

project. You can alternatively go to the Branches

page at

https://github.com/[username]/[repo name]/branches to locate your branch and open a new

Pull Request from there.

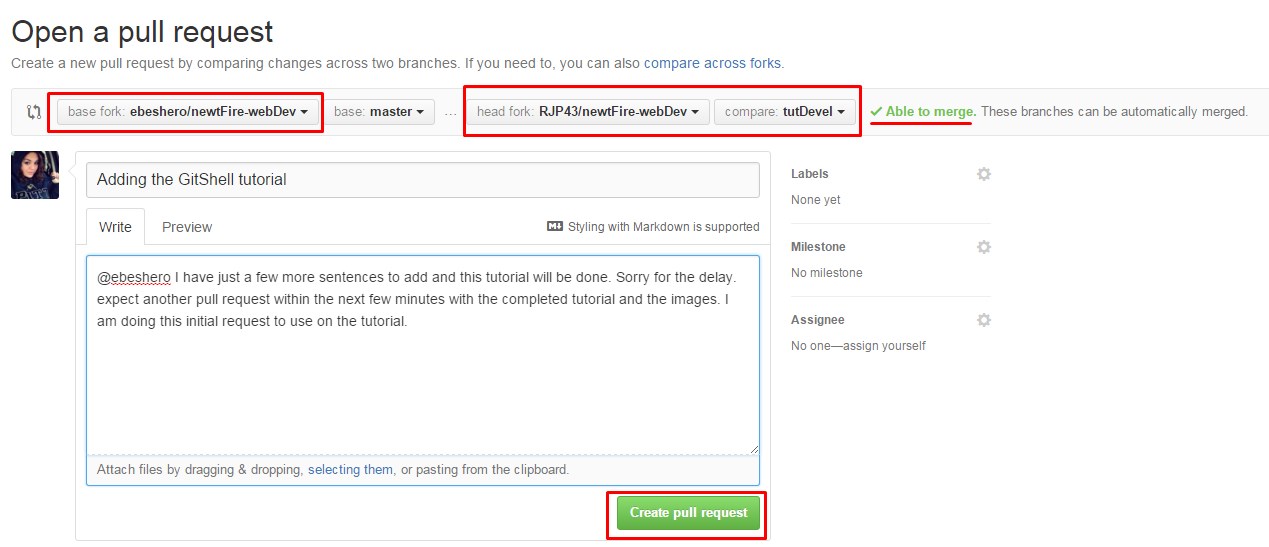

If you click that green Pull Request

button, you’ll see a screen that asks you to

give your Pull Request a title and description. It is always worthwhile to put some

effort into this, since a good description helps the owner of the original project

determine what you were trying to do, whether your proposed changes are correct, and

whether accepting the changes would improve the original project or not. You can also

see a list of the commits in your forked repo’s branch that are ahead

of the

master branch. Should this branch get merged by the project owner, a unified diff

of all the changes will be made.

When you hit the create pull request button, the owner of the project you forked from

will get a notification that someone is suggesting a change with a link to a page that

has all of the information you provided. At this point, the project owner can look at

the suggested changes and merge it, reject it or comment on it. It is possible that the

owner will ask you to rebase from master

and resubmit a pull request. This might

happen if a series of changes were made on the source repo’s master branch that you had

failed to fetch or if such changes were made after you submitted your request. This is

not a problem! Use this very thorough YouTube video

to guide you through how to do this.

Git and GitHub can be a bit confusing for new users, but it makes project management much more robust than the available alternatives, and learning to use it is worth the effort. This tutorial is designed to get you started, and your instructors and mentors are available to advise and help if you get stuck or confused. There are a number of resources online to further your knowledge, some of which can be found at the following links:

Getting Git Right@ atlassian.com

Git - the simple guide